It’s difficult to identify which aspect of the United States’ recent capture of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro was the most audacious. The operation, which took place about three weeks ago, on January 3, 2026, almost certainly violated international law. The Trump administration conducted the strike without Congressional authorization or even a briefing. President Trump repeated his intention that the United States would “run” Venezuela, possibly for years, despite having long campaigned against regime change. We could go on.

While there are many critiques that could be leveled against the Trump administration in light of Maduro’s arrest, this article questions whether corporate capture of the U.S. government may be driving Trump’s increasingly interventionist foreign policy. Before this month’s operation, Trump justified his administration’s action against Venezuela, including striking more than thirty boats in the Caribbean and threatening future attacks on land, by claiming he was targeting drug-trafficking networks. And in fact, Maduro was arraigned on drug-trafficking charges in federal court in New York. But in the immediate aftermath of Maduro’s arrest, Trump started to discuss Venezuelan oil with increasing frequency, leading us to wonder whether getting “wealth out of the ground” was a deciding factor in the operational decision-making.

Critics have long warned that the oil industry holds too much sway over domestic policy. The recent actions in Venezuela should make us question how that outsized influence translates into the foreign policy arena.

Oil and Oil Companies in Venezuela

Venezuela boasts the largest known reserves of oil in the world. Its oil is particularly heavy, dense, and dirty, meaning that the oil requires special refineries and is “among the dirtiest oils in the world to produce when it comes to global warming.” This type of oil can be used for products such as diesel and jet fuel.

In 2007, then-President of Venezuela Hugo Chavez nationalized oil production, shutting out U.S. companies and seizing their assets. Oil majors Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips claim that the Venezuelan government still owes them billions of dollars, and they have been seeking reimbursement since the nationalization. Of the U.S. oil companies, only Chevron remained in Venezuela. Chevron holds a special license from the U.S. government to continue its operations in Venezuela despite U.S. sanctions, the product of a “spirited lobbying effort” throughout 2025. Chevron was the only company to export oil from the country without significant interruption since the United States implemented a blockade on oil from Venezuela in December 2025. Given Chevron’s checkered past in Ecuador, Nigeria and elsewhere, any claim that its involvement would help restore the rule of law or democracy in Venezuela is, at best, ill-informed.

The historical ejection of U.S. oil companies from Venezuela seems to have prompted Trump to frame his interest in oil as a reclamation of the United States’ rightful property. In the press conference announcing Maduro’s ouster, Trump said that “we’re going to take back the oil,” and has since repeated claims that Venezuela stole oil from the United States. Trump’s grand plans might start with pressuring Venezuela to hand over billions of barrels of stockpiled oil, but long-term, he intends for U.S. oil companies to play an integral role in supposedly “revitalizing” Venezuela’s oil industry. Judging from his statements after the operation, in Trump’s ideal world, U.S. oil majors would invest billions of dollars rebuilding Venezuela’s broken down oil infrastructure to massively increase production. This investment would theoretically build wealth for the companies themselves and, depending on the exact parameters of the deal, for the Trump administration.

Questions of Corporate Capture

The full details of the administration’s plan to rebuild Venezuela’s oil industry have yet to take shape. The negotiations and planning over the next weeks and months will provide important insight into the Trump administration’s entanglements with corporate interests in the realm of foreign affairs.

Advocates have long warned about the dangers of corporate influence, specifically from the oil industry, on domestic policy. OpenSecrets reports that the oil and gas sector spent over $100 million on lobbying in 2025. That number is actually down from 2024, which experts say is because the industry wields enough influence over the current government that it does not need to spend as much for favorable policies. That influence comes in many forms, including Trump’s decision to appoint fossil fuel executives to his cabinet, which began in his first term with former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (former CEO of Exxon) and continued with appointments such as current Energy Secretary Chris Wright (former CEO of Liberty Energy, a natural gas fracking company).

In the first year of Trump’s second term, oil companies have already seen major political wins on the domestic front. For example, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act—Trump’s signature legislative achievement of 2025—contained several provisions that would reduce taxes and fees for oil companies. Additionally, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed repealing the so-called Endangerment Finding, which is the determination that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere endanger the health of individuals and communities, forming the basis for many climate change-related regulations.

But what influence do these companies have over foreign policy? It has long been true that the U.S. need for oil impacts our foreign relations. But Trump’s actions in Venezuela go beyond conducting foreign affairs in a manner that avoids a domestic energy crisis. Again, not only did Trump start talking about plans for oil companies to invest in Venezuela immediately after Maduro’s capture, he also reportedly briefed oil executives before and after the operation (although some executives have since refuted that claim). Senate Democrats are worried that the President might be giving too much weight to oil companies’ interests in his conduct of foreign affairs. In a letter sent to several oil executives, the Democrats said that the Trump administration “has explicitly linked its military efforts in Venezuela to the economic interests of the American fossil fuel industry.”

Adding even more complexity to the analysis of corporate influence over Venezuela policy is the fact that, for now, the oil companies do not appear to be jumping at the chance to invest in Venezuela as much as Trump might have hoped. Analysts believe that increasing oil production to previous levels would cost more than $80 billion over six or seven years. Oil companies would be taking a huge risk to invest that money in a politically uncertain environment, where their assets could be nationalized again or a future U.S. president could reverse course on Venezuela policy. When Exxon’s chief executive pointed out these risks to Trump at a meeting with oil company leaders, Trump said the company was “playing too cute” and that he might keep them out of Venezuela altogether.

The Trump administration itself stands to gain from corporations taking a significant role in developing the Venezuelan oil infrastructure. On social media, Trump claimed that he personally would control the profits from the sale of thirty to fifty billion barrels of stockpiled oil. Analysts say that this money could form a “slush fund” for the Trump administration. While this money could be used to benefit the Venezuelan and American people, might President Trump also be tempted to use it for his own pet projects? Given the oil executives’ hesitation to invest, could the situation in Venezuela be an instance of Trump seeing a mutually beneficial opportunity and lashing out when oil companies don’t agree?

We have to ask how much Trump is allowing corporate interests—and his own personal interests—to influence his decisionmaking in foreign relations. The American people deserve a government that is committed to entrenching the rule of law in the conduct of international relations, addressing the climate crisis, operating transparently, and adhering strictly to the principles of government ethics.

Overall, the operation in Venezuela and subsequent negotiations over its oil raise many questions without clear answers. We cannot say with certainty that the operation signals corporate capture of foreign policy. What the events in Venezuela do tell us is that we should carefully analyze the Trump administration’s future foreign policy actions for other signs of corporate influence and governmental corruption, and we should push back on any that seem to place the interests of the American people on the back burner.

Emma Schroer is a Legal Fellow at Corporate Accountability Lab.

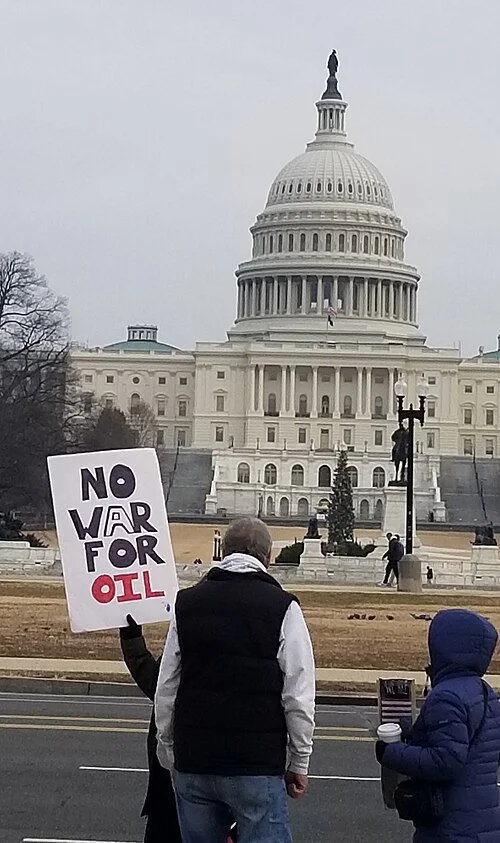

Cover photo by Mike Licht, “No Blood for Oil,” 2026, CC License 4.0.