Corporate Accountability Lab Blog

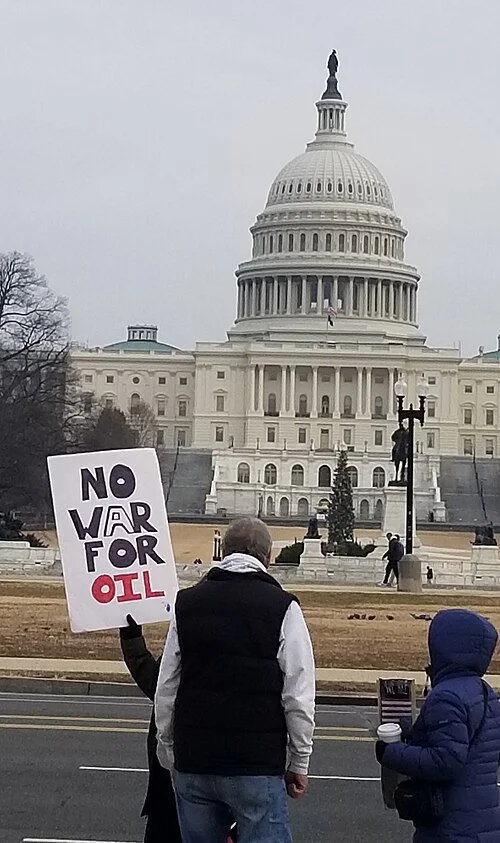

While there are many critiques that could be leveled against the Trump administration in light of Maduro’s arrest, this article questions whether corporate capture of the U.S. government may be driving Trump’s increasingly interventionist foreign policy. Before this month’s operation, Trump justified his administration’s action against Venezuela, including striking more than thirty boats in the Caribbean and threatening future attacks on land, by claiming he was targeting drug-trafficking networks. And in fact, Maduro was arraigned on drug-trafficking charges in federal court in New York. But in the immediate aftermath of Maduro’s arrest, Trump started to discuss Venezuelan oil with increasing frequency, leading us to wonder whether getting “wealth out of the ground” was a deciding factor in the operational decision-making.

Scaling up climate civil litigation against corporations, the largest greenhouse gas emitters, can hold them accountable for their actions and mitigate additional harms. Climate change litigation can drive down greenhouse gas emissions; push for better responses to the effects of climate change; or provide compensation to impacted communities. By leveraging the creative potential of the law and prioritizing legally viable, replicable, and impactful strategies, litigators may be able to secure remedies that effectively change corporate behavior and create institutional change.

The climate crisis calls for an all-hands-on-deck response, and litigators from various fields have a critical role to play. For those still on the fence about whether to get involved, here are five reasons why now is the time to bring your unique skill set to the climate fight.

In March 2025, four Indonesian fishers filed a lawsuit in California against Bumble Bee Foods, a major U.S. tuna company. The fishers claimed Bumble Bee had violated the prohibition on forced labor under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA).

On November 12, 2025, a district court allowed the case against Bumble Bee Foods to continue beyond the motion to dismiss stage. This is an important decision, making it more likely that the four plaintiff fishers – who faced severe deprivation and abuse while out at sea – will eventually receive a remedy.

A little over a week ago, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson publicly called on the United Nations Human Rights Council to send independent experts to Chicago to investigate the ongoing abuses at the hands of federal immigration officials. Thirteen months ago, we would not have believed that our Mayor would be calling on the United Nations to investigate the federal government waging war on our home city. Given the bloody history of this country, it would not be correct to say this is shocking. More so, the swift descent to where we are now, barely ten months into this administration’s reign of power, is profoundly unsettling. Whatever rule of law the United States could ever claim to have—even if it only benefitted the privileged—is gone. Despite district courts’ restraining orders, federal agents continue to use chemical weapons, projectiles, and violence against their own people. Our own government appears to be wantonly trampling on our rights; and we are barely ten months in.

That the Fanjuls would donate to President Trump’s construction project did not come as a surprise to those of us at CAL who have been following the saga of sugar from the Dominican Republic that is tainted by labor abuses. The Fanjul family operates a vast sugar conglomerate comprising the likes of Domino Sugar, Florida Crystals, and Central Romana Corporation, a massive sugar producer in the Dominican Republic that exports to the United States and that workers and human rights advocates have denounced for decades for its use of forced labor. Central Romana has already benefited from the “first family of corporate welfare’s” close relationship to President Trump.

Following decades of failed regulatory action in Ghana that has allowed chocolate companies to continuously undercut cocoa farmers, in October 2024, a group of 30 farmers brought four demands before the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD). On October 31, 2024, Corporate Accountability Lab (CAL), the University of Ghana School of Law, and Civic Response (Ghana) submitted a grievance to COCOBOD’s grievance and redress mechanism on behalf of 30 cocoa farmers. Yet in the year since filing, COCOBOD has done little to respond to the documented violations – or to improve conditions for cocoa farmers or protect the environment in Ghana.

The cocoa industry is complex, and volatile market prices and companies’ responses can easily grab consumers’ attention this Halloween season. But we should not simply focus on big corporations and market forces and ignore the human reality behind the dollar sign. Climate change, deforestation, and disease are doing more than raising the cost of Halloween candy; they are threatening the livelihoods of the many farmers who helped make the season so sweet.

With her recent passing at 106 years old, Jean Dolores Schmidt, a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM), left behind a spirited legacy reaching far beyond the basketball court. Leading with a steadfast commitment to people and the planet, Sister Jean’s community partnered with CAL to integrate a groundbreaking legal mechanism into the supply chain contracts for goods produced with her image and likeness, or bearing any Sr. Jean quotes like her classic “Work, worship and win.” CAL, which had recently been established as a legal design lab to imagine new ways to uphold human rights in global supply chains, was grappling with the fact that while supplier codes of conduct were proliferating across industries to address human rights risks, workers reported few actual changes on the ground. CAL saw this problem as an opportunity: those well-meaning codes could be made enforceable by workers and impacted communities, the people who have the most to gain from their enforcement, and the most to lose when their terms are ignored. We found a natural teammate to test this idea in Sister Jean.

In March 2023, CAL sued açaí multinational Sambazon under Washington D.C.’s consumer protection statute for misleading consumers about its sourcing practices. Sustainability and ethical sourcing constitute cornerstones of Sambazon’s marketing, while açaí production continues to be a process rife with hazardous child labor. This summer we have successfully overcome efforts to dismiss the case on procedural grounds, and we are pushing forward to hold Sambazon accountable to the truth. This blog post first describes why this decision is a win for CAL and broader efforts to hold companies accountable for misleading consumers. It then presents insights from two investigations in Brazil which underscore that hazardous child labor persists as a feature of an industry.

Brazil is the world’s largest beef exporter and the third largest exporter of an increasingly profitable byproduct: beef tallow. Behind this multibillion dollar industry are supply chains riddled with forced labor. Major corporations, including JBS, Minerva, Marfrig, Diamond Green Diesel (DGD), FASA Group, and Aramco Americas profit from this forced labor. On July 24, 2025, Corporate Accountability Lab’s (CAL) published a report, Bullsh*t: Forced Labor in Brazil’s Beef and Tallow Supply Chains, which details these abuses and traces the supply chain from fifteen ranches into the United States. That same day, CAL submitted information to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) under Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (Section 307), requesting they block all imports of beef tallow – a beef byproduct – produced with forced labor.

After nearly a decade of legal back-and-forth, a major decision from the UK High Court has moved the case against Shell plc (Shell) and its former Nigerian subsidiary one step closer to trial. On June 20, the Court ruled that the Bille and Ogale communities in Ogoniland in the Niger Delta can pursue claims for environmental harm dating back decades, rejecting Shell’s attempt to escape liability based on procedural technicalities. For the tens of thousands of residents living with the aftermath of oil spills, this ruling opens a path forward. And for others watching from across the globe, where multinational corporations have extracted resources and left destruction behind, it’s a moment worth paying attention to.

This blog post provides an update on the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPRA) case against five defendant seafood companies: Phatthana Seafood Co., Ltd.; S.S. Frozen Food Co., Ltd.; Doe Corporations; Rubicon Resources, LLC; and Wales & Co. Universe Ltd. It provides an overview of the harms workers faced, a history of the case, and an interpretation of the latest TVPRA amendment currently impacting this case. It concludes by discussing how the Ninth Circuit can rectify its mistakes and provide justice to the seven individuals whose lives were devastated by these corporations.

On March 12, 2025, four Indonesian fishers filed suit in San Diego, California, against Bumble Bee Foods. They claimed they were victims of forced labor, human trafficking, and debt bondage in violation of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPRA). This case is the first human trafficking case brought against a U.S. seafood company for forced labor at sea.

On January 21, 2025, President Bola Tinubu of Nigeria met with members of the Ogoni community of the Niger Delta to discuss the potential resumption of oil drilling within their lands. Oil extraction was halted over two decades ago, after the Ogoni people organized to end Shell’s destructive presence within their community. Ogoniland, which was once home to a rich tapestry of biodiversity, is now one of the most polluted regions on the planet.

A recent report has found that MSC-certified fisheries work with fishing vessels where incidents of forced labor have been reported by fishermen. The Outlaw Ocean Project documented forced Uyghur labor in ten MSC-certified facilities in China. A 2023 report by a coalition of international environmental non-profit organizations has further critiqued the MSC for its lax environmental standards, lack of labor protections, and deception of consumers. In spite of all this evidence, the MSC continues to fail consumers by allowing them to believe that buying MSC-certified products is the sustainable option when, in reality, the fish coming from MSC-certified facilities were procured and processed in a manner comparable to those originating from non-certified facilities. Certification schemes like the MSC need either to effectively protect workers’ rights and the environment or remove themselves from occupying the space of a more effective alternative, such as a union or worker-driven model.

BAP is a third-party certification scheme that claims to certify each step of the aquaculture production chain, including farm, feed, hatcheries, and processing facilities. BAP touts itself as being one of the “easiest ways to know that your seafood was produced in a safe, responsible, and ethical way.” In reality, BAP-certified shrimp production processes are rife with labor and environmental abuses.

Ghana is the second largest producer of cocoa in the world, home to over 800,000 smallholder farmers who make up about 60 percent of Ghana’s agricultural workforce. Despite the massive profits that global chocolate companies earn, poverty is pervasive in Ghana’s cocoa-growing communities. According to the 2022 Cocoa Barometer, an overwhelming majority of farmers and their families live in poverty: the average cocoa farmer earns between $0.40 and $0.45 USD per day, whereas the living wage in Ghana is estimated as of 2022 to be $13.5 USD per day. Meanwhile, chocolate companies have been making record profits despite the pandemic and global inflation.

The problem with the cocoa commodity price spike is not the increased price. Cocoa should be priced higher! But more of that value needs to go to the farmers who grow it. Outside of the commoditized market that supplies bulk quantities of cocoa to corporations such as Nestlé and Mondelez, alternative supply chain models already exist. Some smaller “premium” chocolate companies contract directly with farmers, paying up to $12,000 per metric ton of cocoa. They pay the premium price to ensure a supply of beans that are harvested by ethical, well-compensated laborers on an environmentally sustainable farm.

Beginning with the history of the case, this post covers the facts and implications of the recent unanimous verdict reached by a federal jury in In re Chiquita. The first part of the post details Chiquita’s history in Colombia, the human rights abuses associated with its relationship with the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), and the litigation that followed. The second part of the post considers the immediate future of this case as well as its systemic implications with a particular focus on this verdict’s implications for the use of state tort law in human rights litigation.

The United States is both a world leader in the protection against forced labor – and one of the world’s most practiced and committed violators. This hypocrisy is due to an inherent contradiction in U.S. law: while it is illegal to import goods produced with forced or prison labor, it is not illegal to produce goods using prison labor or export goods produced in such a manner. This inconsistency means that incarcerated workers in the United States produce products that can – and likely are – exported to other countries, where they can be sold, perhaps even labeled as “Made in USA.”

Canada’s long-awaited, Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act (Act) went into effect on January 1, 2024. While it is largely a disclosure law, it also makes Canada the first country in the world to ban the importation of goods made with child labor—a bold and controversial move, discussed further below. In this blog post, we provide an overview of the two key elements of the Act and then explain the Act’s limitations compared to other supply chain legislation.

It has only been a few weeks since we published our report and already we are seeing shifts in the industry. In the coming months, we hope to see more improvements for workers and their communities. The first step towards change is acknowledging the problem. The attention on the industry and the acknowledgement from many U.S. retailers and distributors that they need to look into their supply chains, is a beginning. As we move forward, it is imperative that companies – both U.S. and Indian – do more than make appropriate statements. They must implement changes to upend the prevailing pattern of abuse.

While the just transition is gestured at as a solution to the climate crisis, the extraction of critical minerals that underlies the transition often violates human rights and causes environmental damage, underscoring the limitations of the growth-focused economic model. A truly just transition is ultimately a regenerative one, of ecological resilience and reduced resource consumption. But until that can be achieved, green energy supply chains must be improved. Workers and others directly impacted by the energy transition’s thirst for critical minerals must be treated with dignity, agency, and autonomy.

This year, states will begin implementing a global minimum tax rate of fifteen percent on multinational corporations with more than €750 million (about $810 million) in revenues. If these tax reforms succeed in increasing tax revenues across the approximately 140 implementing countries as they intend, these additional funds could be used to advance the social and economic rights of their citizens, especially for the most vulnerable populations, including those whose rights have been abused by corporations historically. However, the coming tax reforms are still so riddled with gray areas regarding form and function that it is too early to call the initiative a victory in corporate accountability.

Across Nigeria, children, teenagers, and adults spend long days working on cocoa farms. Samuel* is one of these workers, a teenager who looks to be under eighteen – although he refused to tell us his age. Like the other workers on the farm, Samuel spends the day using a machete to chop down cocoa pods from trees, cut them open and remove the cocoa beans for drying and fermenting – dangerous work for anyone, but especially for children.

On November 22, 2023, the United Kingdom’s (UK) High Court found that 13,000 Nigerian fisherman and farmers from the Ogale and Bille communities in the Niger Delta can bring landmark human rights claims against Shell for breaches of the communities’ right to a clean environment. Shell, a British-Dutch company, first began extracting oil from the biodiverse Niger Delta in the late 1950s under a joint venture it established with the Nigerian government just four years before Nigeria gained independence from Great Britain.

In October 2023, a landmark war crimes trial began in Sweden: the first prosecution in Swedish history of corporate executives for aiding and abetting war crimes. The trial opened to intense public interest – likely to intensify as it unfolds over the next two years. And for good reason. In many ways, this trial is legally unusual. The two corporate executives, Chairman Ian Lundin and former CEO Alex Schneiter, worked for the Swedish oil giant, Lundin Energy – previously known as Lundin Petroleum and Lundin Oil.

Although some think of chattel slavery as a practice of the past, it is a daily reality for far too many. In Mauritania, there are an estimated 149,000 individuals still enslaved, out of a population of under five million. In addition to raising alarming concerns for human rights accountability over private individuals perpetrating slavery in Mauritania, this reality brings to light important issues for companies who source agricultural goods from local farmers who have historically relied on slave labor. These companies’ responsibilities are heightened in a country with a deep-rooted legacy of slavery.